On July 27, 2017, we began our tour through a trinity of prominent Norse dragons with Nidhogg, the corpse-eating serpent of Niflheim. Turning to the second in the series, we’ll emerge from the misty underworld and travel to Nidavellir (sometimes called Svartlheim), the realm of the dwarves. [1] For our second dragon, Fafnir, began his life as a dwarf.

1895 illustration from the Prose Edda, depicting two dwarves.

In Norse mythology, the world came into being when Odin, the All-Father, and his brothers, Vili and Ve, slew the giant, Ymir, and created the land and the sea from his flesh, blood, and bones.[2] The dwarves, or devrgr, were created from the body of Ymir, given the likeness and understanding of men, and “occupied [Yimir’s] flesh like maggots.”[3] They dwelled underground, in labyrinthine cities beneath mountain.

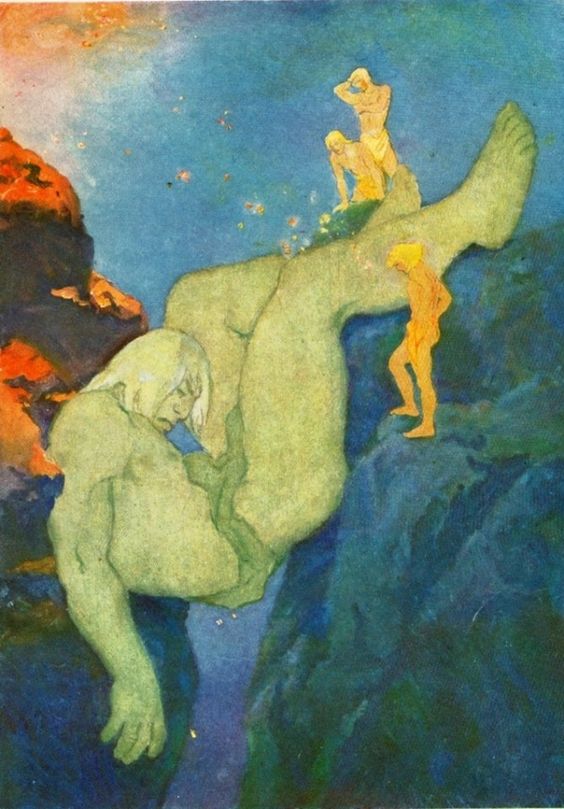

“Odin, his brothers, and the giant, Ymir,” by Katharine Pyle (1930).

Dwarves were best known for their craftsmanship, so they often figured into tales as the makers of legendary weapons and treasures.[4] They bestowed some of these treasures upon the gods, and these items became important symbols for the recipients. For instance, Odin was given a golden arm-ring called Draupnir, which means “dripper.” Every ninth night, Draupnir produced eight equally lovely arm-rings. The dwarves also crafted Odin’s spear, Gungnir, which always found its mark and penetrated any surface. An oath made on Gungnir could not be broken. For Frey, the dwarves made a ship called Skidbladnir, for which a fair wind always blew. Skidbladnir could be folded up into a silk scarf and tucked into a pouch for easy storage. For Thor, they created his infamous hammer, Mjollnir, the lightning-maker, which was unbreakable, never missed its target, always returned to his hand, and could change its size to be more easily concealed on his person.

Thor wielding Mjollnir in an 18th century Icelandic illustration.

The dwarf who is the particular subject of this blog post was not known for his wondrous creations so much for becoming a symbol of the corrupting force of greed. You see, before he was a monster, Fafnir was one of the three sons of the dwarf, Hreidmar.[5] Of Hreidmar’s progeny, Regin was the craftsman, Fafnir was the strong fighter, and Otr was the hunter. In addition to his hunting abilities, Otr was a shapeshifter who liked to take the form of an otter and swim in deep pools.[6] One day, the god, Loki, happened upon Otr. He mistook him for an actual otter and killed him. He and the two gods he traveled with, Hoenir and Odin, skinned the otter and kept his pelt. They decided to go visit Hreidmar. Only, when they showed him the pelt, Hreidmar was justifiably furious, recognizing it as the skin of his slain son. He took the gods captive and demanded enough gold to cover every inch of the pelt as ransom.

“Loki with the Rhinemaidens” by Arthur Rackham.

Loki, ever the cleverest of the gods, went back to the pool, where a dwarf named Andvari liked to swim in the form of a pike. He caught Andvari in a net and refused to release him until he surrendered his gold. Andvari eventually agreed. Still, he attempted to hide one golden ring for himself. When Loki demanded the ring, too, Andvari pronounced, “My treasure and this ring will be the death of all who own it.”

Loki delivered Andvari’s treasure to Hreidmar, using it to cover every inch of poor Otr’s pelt. Only, one hair was still left uncovered. Not to be cheated, Hreidmar demanded that the bargain be fulfilled and that last hair be concealed, as well. Grudgingly, Loki produced that last golden ring and added it to the pile. With that, the gods were released, and went on their way. But the tale was not over, because there was still Andvari’s curse to consider.

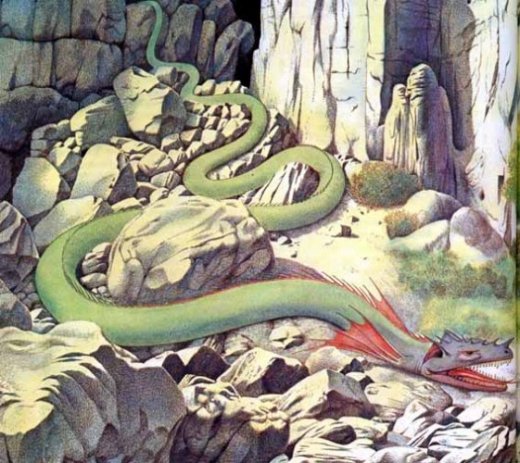

“Fafnir” by Giovanni Caselli (1978).

Fafnir became obsessed with the notion of stealing his father’s gold. [7] He ultimately conspired with Regin to murder their father. Only, Fafnir had no intention of sharing the wealth. He spirited the treasure away to Gritaheid (or Gnita Heath). Making it into a bed, he curled up on top of his stolen gold and transformed into a monstrous dragon.

In J.R.R. Tolkien’s translation and arrangement of the Elder Edda, it is said of Fafnir:

Men sing of serpents

ceaseless guarding

gold and silver

greedy-hearted;

but fell Fafnir

folk all name him

of dragons direst,

dreaming evil.[8]

Poison mists were said to emanate from Fafnir’s cave, as he was armed with both venom and fire.[9]

Regin was not so daunted by Fafnir’s new form that he intended to let the gold get away. He enlisted as his champion the young hero, Sigurd. Sigurd was the son of Sigmund, a legendary warrior who wielded a sword given to his family by Odin, himself.[10] Only, by the time Sigurd was approached by Regin, the sword had been shattered in Sigmund’s final battle. As Sigmund died, he had bidden his queen to gather up the fragments, foretelling:

Thy womb shall wax

with the World’s chosen,

serpent-slayer,

seed of Odin.

Till ages end

all shall name him

chief of chieftains,

changeless glory.Of Grimnir’s gift

guard the fragments;

of the shards shall be shaped

a shining blade.

Too soon shall I see

Sigurd bear it

to glad Valholl

greeting Odin.[11]

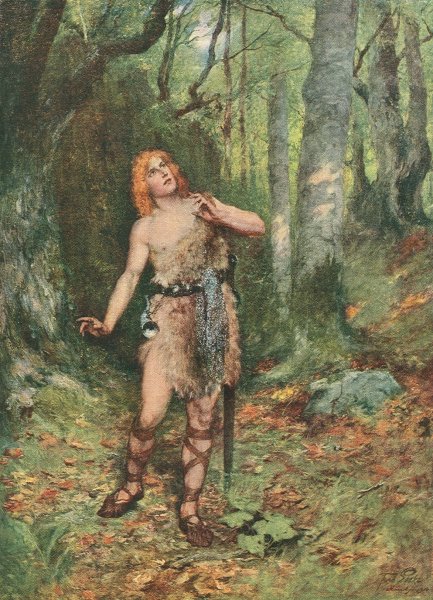

Sigurd was every bit the warrior his father had foretold, but he was not immune to Regin’s wiliness. Regin persuaded him to take on the dragon, Fafnir, in return for a share of the gold and the promise of a blade fit for the task.[12] However, when Regin tried to create a sword for Sigurd, each time, Sigurd struck the blade against Regin’s anvil and shattered it. Finally, Sigurd provided him with the pieces of his father’s sword, which the dwarf forged into a new blade. This sword, called Gram, did not break against the anvil. Regin also showed him a herd of horses, from which Sigurd chose his grey steed, Gami.[13] Gami was the offspring of Odin’s horse, Sleipnir, and certainly a proper steed for dragon-slaying. With the youth so-armed, Regin advised him to go to the river near Fafnir’s heath and dig a trench close to the shore.[14] When the dragon came down to drink, Sigurd could plunge his sword into the dragon’s soft underbelly, killing him so that Regin and Sigurd could claim his treasure.

“Sigurd Fighting Fafnir” by Arthur Rackham.

Sigurd did as the dwarf advised, hiding in the trench as the enormous coils of the serpent passed overhead.[15] He then stabbed upwards with Gram, slashing open the dragon’s belly. Fafnir lashed about in agony, causing the ground to tremble with his death throes. As the light faded from his eyes, the dragon asked Sigurd who he was and who had put him up to this task. When Sigurd answered, Fafnir warned him that anyone who owned his treasure would lose his life.

Afterwards, Regin arrived and congratulated Sigurd on his kill.[16] He then asked Sigurd to cut out the dragon’s heart and roast it for him. Only, as Sigurd was doing so, he burned his hand checking to see if the meat was cooked. Reflexively, he put his finger in his mouth. Upon tasting Fafnir’s blood, Sigurd understood the language of the birds in the nearby trees, who were discussing how Regin intended to kill Sigurd. When Regin returned to the fire, Sigurd lopped off his head. He then ate Fafnir’s heart himself, gathered up the treasure, and rode away, on to other adventures.

“Sigurd Being Instructed by the Birds” by Ferdinand Leeke

Fafnir’s prophecy ultimately came true. Sigurd was slain by his brothers-in-law, who wanted his gold for themselves.[17] In the violence and bloodshed surrounding the gold, the brothers-in-law were also slain, along with Sigurd’s beloved, Brynhild, and the son they had together. Sigurd’s widow, Gurdrun’s, second husband and his two sons also perished. Other casualties of the curse included Gudrun’s third husband and his three sons, and a king and a prince, besides.

This myth is widely interpreted to be a tale about the dangers of avarice, with Fafnir’s monstrosity being symbolic of the moral repugnance of greed and its potential to damage both an individual and society.[18] Ultimately, Fafnir became the model for another famous dragon, Smaug, the gold-hoarding dragon that appears in J.R.R. Tolkien’s book, The Hobbit.[19] Smaug’s popularity ensured that subsequent fantasy tales incorporated similar greedy dragons. It has been noted that Sigurd tasting Fafnir’s blood and gaining knowledge of the language of the birds fits into a trope in which the dragon-slayer eats some part of the dragon and takes on some of its attributes.[20]

Ultimately, while he might not have been born a dragon, Fafnir became both famous in his own right and a model for subsequent dragons. Only, being known for greed, patricide, and as the victim of fratricide are dubious claims to fame.

Tune in next time for our final dragon, Jörmungand, the Midgard serpent, and the discussion regarding which of these winged villains provided the inspiration for the beastie in my short story, “Jenny Redcape.” If you can’t wait to find out, pick up a copy on Amazon today and see for yourself!

Buy your copy here.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Gaiman, Neil. “Yggdrasil and the Nine Worlds.” Norse Mythology. 1st ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2017. Print. pp. 38. (hereinafter “Gaiman.”) (The cited page numbers refer to the ebook edition.) See also McCoy, Daniel. “Dwarves.” Norse Mythology for Smart People. N.p., 2012. Web. 10 Aug. 2017.

[2] Gaiman. “Before the Beginning and After.” pp. 29-31.

[3] “The Role of Serpents and Dragons in Norse Mythology.” The Atlantic Religion. N.p., 2014. Web. 9 August 2017. (hereinafter “The Role of Serpents and Dragons in Norse Mythology.”)

[4] Gaiman. “The Treasures of the Gods.” pp. 45-67.

[5] Evans, Jonathan. Dragons. East Sussex: Ivy Press Limited, 2008. Print. p. 155. See also Rose, Carol. Giants, Monsters, And Dragons. Santa Barbara, CA.: ABC-Clio, Inc, 2000. Print. pp. 117.

[6] Evans at 155.

[7] Evans at 155. Rose at 117.

[8] Tolkien, J. R. R, and Christopher Tolkien. The Legend Of Sigurd And Gudrún. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009. Print. pp. 101.

[9] Tolkien at 101, 108.

[10] Tolkien at 72-98.

[11] Tolkien at 96.

[12] Tolkien at 99-106; Rose at 117; Evans at 156.

[13] Tolkien at 107.

[14] Tolkien at 108-09; Rose at 117; Evans at 137.

[15] Tolkien at 108-10; Evans at 138.

[16] Evans at 139; Rose at 117; Tolkien at 111-15.

[17] Evans at 140.

[18] Evans at 74, 131.

[19] “The Role of Serpents and Dragons in Norse Mythology.”

[20] Allen, Judy, and Griffiths, Jeanne. The Book Of The Dragon. London: Orbis Publishing, 1979. Print. pp. 123-24.

Pingback: The Unusual Suspects: Norse Dragons (Part 1) | amandakespohl

Pingback: The Unusual Suspects 3- Jormungand, The Midgard Serpent | amandakespohl